Taking care of a dying person is draining, but I can fend off depression by concentrating on the Boedeker family. This tack triggers another realization, adding guilt to my panoply of emotions. I realize that I am a voyeur, my mind’s eye loupe is peering into their lives without permission. Should I tell Sarah?

I email every Ancestry.com member who has a solid Boedeker tree, solid meaning having more documented information than I have. I might get lucky. Again, I surf the web, looking for anything on Bump Boedeker.

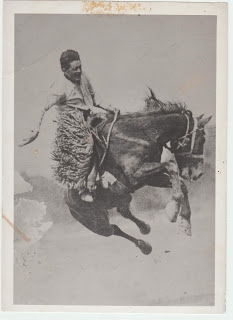

Then I see him, the subject of a painting entitled “The Bronc.” Mouth agape in exhilaration but right arm downward in virtual repose, Bump Boedeker sits snugly atop a contorted, bucking horse, strands of his woolies and scalp hair flung counter to the horse’s hard twist. As the painting’s artist John Foster explains, Bump’s wild bronco ride was captured on film in 1932 in Pinedale, Wyoming. By the late 1950s, Foster asserts, the photo was known in that area to be one “of the best dynamic photos of all time, showing a man breaking a bronc.” In Foster’s words, nobody handled a horse better than Bump Boedeker.

Foster also connects Boedeker Butte to Bump and his family, the landmark’s location as being several miles north of Dubois, just above Bog Lake. He claims Bump was the father of a deceased friend who was the cook on the Red Rock Ranch in Dubois, Wyoming, where the artist had worked breaking horses. Immediately I decide to contact Foster. I want a copy of the photograph and more importantly, information. A story is emerging.

I did it! I contacted John Foster. He was a teenager in 1957 when he learned how to wrangle horses at Red Rock Ranch. Besides room and board, he earned his living, breaking colts for trail rides. He wryly tells me he also had to break and train the dudes who arrived at the ranch for entertainment. Red Rock Ranch was a stopping place for tourists who traveled to Teton National Park or Yellowstone National Park when they weren’t riding older, savvy horses plodding along with their noses to the trail. So how did he happen to acquire a photo of Bump Boedeker, I want to know.

The deceased friend, a cook at Red Rock Ranch, was Dot Lewis. I recall this name on Ancestry. Dot wasn’t the daughter of Bump Boedeker—she was his sister, real name Effie Mae! The Boedeker family seems to have an affinity for nicknames. Foster mentions a Freddy, Dot’s son-in-law and a young WWII veteran, also working at Red Rock Ranch. Foster and Freddy Stevens became fast friends, and Foster acquired the photo directly from Freddy’s family.

I study the photo closely. A professional photographer had to have taken the action shot. Online I search other photos taken in Wyoming circa the 1930s. Rather quickly one name emerges—Charles Belden, famed Wyoming photographer. In Meeteetse, Wyoming, the Charles Belden Photography Museum features his works, many of which document daily life on the Pitchfork Ranch from about 1914 to the 1940s. I gaze at Belden’s photos, some quite similar to Bump Boedeker’s 1932 bronc ride in Pinedale, Wyoming, a circuitous 282-mile drive south from Meeteetse, circumventing the Wind River Indian Reservation. I decide to contact the museum, emailing the image.

In no time at all, the museum director sends me images of Belden’s mark and signature. Bump’s photo has no mark, and Belden typically signed the matting of photos he gave as gifts or sold. Could Foster’s unmatted photo be a Belden, I ask? Certainly, the director replies, but without a mark, the photo’s authenticity can not be proven. No matter. A handsome photo of Bump Boedeker exists, in an activity no one guessed.

Contacting John Foster again, I order a giclée of Bump Boedeker on his horse, beg for a copy of the original photo, and email questions about Bump and Hank Boedeker. How will Sarah feel, learning this new dimension to her great-grandfather? I wonder if I am making a mistake.