When I was a kid at Halloween in El Paso, Texas, I often resorted to the easiest costume I could put together, short of cutting two holes in a white sheet and trick-or-treating as a ghost. While many of my peers often dressed as beatniks, my friends and I would dress as hoboes. Easy. Ragged clothes, smudged cheeks, holey tennis shoes, a bag on a stick, and voila! We didn’t intend to be cruel. After all, some schools had Hobo Day where everyone dressed up. With Roger Miller singing “King of the Road” on our transistor radios, we were inspired! Going door to door, we begged for our handouts, Halloween treats.

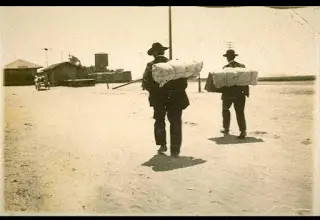

I also had no idea that part of the ‘60s lexicon originated from the original hoboes, or bindle stiffs (called thus because of the bag or bindle they carried on their backs). My friends and I used their words, including tramp (hobo), ditch (to get rid of something), can (police station), fink (or in our case, a “rat fink,” a person who snitches), flop or dump (place to “hang.”) Who knew? I certainly didn’t.

Not until I was deep into my California research of Frank Little did I realize the significance of the hobo culture, how it originated, its connection to me, and, of course, my famous hobo-agitator uncle. I must admit—I had hated this historical period, that is, early twentieth century with its industrial growth, labor unions, and robber barons. When I taught US history many years later, I was still uninspired to dig deeply in the era. Until Frank.

Just like Frank, I grew up in an anti-establishment period. The United States was experiencing an unpopular war in the 1960s, in contrast to years between 1914 and 1917, when Americans were deeply divided about getting into World War I. Many American workers had found themselves displaced during Reconstruction, families often struggling to start all over again after the Civil War. Their children and grandchildren, faced with family debt and hopelessness, often tramped, becoming part of a temporary labor force across the country. Throw in two economic panics (1893 and 1907), a heavily-enlisted immigration force to fuel the American industrial revolution, mechanization, and labor unrest, and a growing population of unskilled migratory workers hit the road seeking work.

Many of these men had left homes in the East or were recent immigrants who found the American dream out of reach. If one were to ask for an inventory of skills in a hobo camp or “jungle,” a diversity of trades would be found. American economic conditions between 1907 and 1914 had compelled even skilled men to search for seasonable jobs, their homes and families often lost. Some preferred drifting with no responsibilities and required little to satisfy their needs. However, walking was not their preferred method of drifting from job to job.

A recent television car advertisement shows a dreamy-faced young woman traveling in an open box car, her Labrador retriever beside her. Freedom. Then her daydream cuts to reality, sitting in a wonderful car that can take her on an open road deviating away from the train’s tracks. While this scene is enticing, riding the rails was a dangerous endeavor for Wobblies who often became hoboes.

Freeloading train travel had inherent dangers. Because railroad workers were unionized, a paid-up union membership card usually protected men, including IWWs, and provided them with free passage. Brakemen otherwise booted off freeloaders without union affiliations. But trains also carried bootleggers and hijackers who stole hoboes’ small valuables at gunpoint. Later, railroad detectives patrolled to make sure “stiffs” could not board idle trains. Jumping on and off slow-moving trains was dangerous in itself. Some men died or lost limbs. As an example, in 1913 my uncle miscalculated a jump onto a Western Pacific train and badly sprained his ankle.

Like Frank, hoboes were typically apolitical and rarely stayed in one place long enough to vote. While AFL’s Samuel Gompers asserted that the lot of the migratory worker was worse than slavery, the AFL did little to help migrants who did not vote. Thus, the Industrial Workers of the World—which did not discriminate ethnicity, creed, color, or gender—captured their memberships.

When hoboes did stay in one place, it was a “jungle” or camp, often near railroad tracks and water, where a fluctuating population could find the most basic needs for survival or quickly board a train for work. In describing the migratory farm worker, Frank once wrote, “When you see one tramping along the road, he generally has a load on his back that the average prospector would be ashamed to put on a jackass. In fact, most of the jackasses would have enough sense to kick it off.” During harvest season, he added, a steady line of these bindle stiffs “tramping down the highway” begged for the “right to work to earn enough to buy a little grub, take it down to the jungles by a river or beside an irrigation ditch, and then cook it up in old tin cans which their masters had thrown away.”

Recently, as we drove through Fresno’s downtown streets, I wondered about this new generation of bindle stiffs, the homeless we saw living in an enormous tent-and-cardboard colony, its blue-and-tan tarps fluttering in soft warm breezes. Were they workers, or “occupiers”?

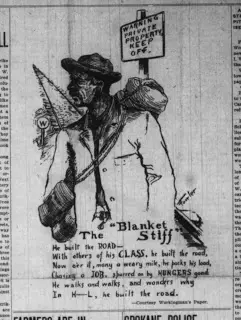

Just a hundred years earlier, a poster hung in a Fresno’s IWW hall. A drawing of a bindle stiff walking down a railroad track with his bundle over his arm read: “He built the ROAD with others of his CLASS, he built the road and now for many a mile he packs his load and wonders why the H–ll he built the road. The “Blanket Stiff.”