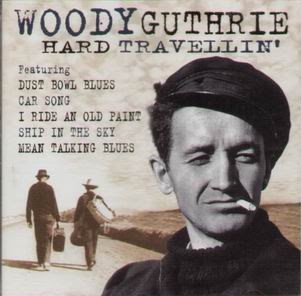

I’m busy preparing my presentation for the High Plains Book Festival so no new post. Since today is the anniversary of American folk singer and writer Woody Guthrie’s death, I honor him, reposting a blog from my www.franklittleandtheiww.net “Chasing Rabbits” page:

I first came across Woody Guthrie while researching another lyricist, IWW Joe Hill, whom Guthrie had honored through verse. Both men composed lyrics for working class audiences, though a generation apart. But unlike the Swedish-born Hill, Guthrie was an American product, born in Okemah, Oklahoma, the son of a cowboy-politician and musical mother. And like my Oklahoman uncle Frank Little, he witnessed his family’s economic collapse; Frank’s, after the Panic of 1893 and years of drought, and Guthrie’s, after Oklahoma’s oil boom collapsed. So, it is no surprise that all three men—Guthrie, Hill, and Little—preached populist sentiments that appealed to workers.

The second time Woody Guthrie’s name popped up was during an academic review of my manuscript, Frank Little and the IWW: The Blood That Stained an American Family. An Oklahoma historian strongly supported its publication stating, though he personally was a “left wing” kind of guy, he was reminded of a story about Woody Guthrie when Guthrie was accused of being too far left-wing. Guthrie had responded in his best Okie drawl, “Aw, left-wing, right-wing, chicken wing, it don’t make no difference to me, I just support programs that help my people.” I loved that. The professor went on to say that thoughtful readers of any point on the ideological spectrum could see the importance of my book in modern day when “red state” Oklahoma means conservative Republican, but during Frank’s life, it meant far left, as in “reds” or socialists.

This analysis got me to thinking. Guthrie’s reminder that no matter our philosophical differences or our political perspectives, most Americans want the best for their brothers and sisters. Frank Little was no different, and his passion for helping workers and their families was sincere. It is the context in which he lived that colors his historical prominence, thus requiring an informed, educated mind to evaluate his contributions in American history.

Like Frank, Woody Guthrie was a hobo during a period of his life. He had headed west looking for work during the Depression, riding freight trains and walking the open road, all the while observing folk he encountered daily in tent jungles. Also like Frank, Guthrie found native antagonism toward these same itinerant farm workers who had invaded the Golden State looking for any type of work.

Ultimately Woody Guthrie found his soapbox—on a radio show. A Guthrie family organization states that, through radio airwaves, Guthrie “developed his talent for controversial social commentary and criticism. On topics ranging from corrupt politicians, lawyers, and businessmen to praising the compassionate and humanist principles of Jesus Christ, the outlaw hero Pretty Boy Floyd, and the union organizers that were fighting for the rights of migrant workers in California’s agricultural communities, Guthrie proved himself a hard-hitting advocate for truth, fairness, and justice” [woodyguthrie.org]. Later Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and others from his circle, were targeted for their activist stances on such issues as the right to unionize, equal rights, and free speech. Sound familiar?

We all know Woody Guthrie’s song, “This Land is My Land.” But I find that his “Dust Bowl” ballads best liken his views to Frank Little’s:

Wherever little children are hungry and cryWherever people ain’t freeWherever men are fightin’ for their rightsThat’s where I’m a-gonna be, MaThat’s where I’m a-gonna be

From “Tom Joad”

Another life cut short, Woody Guthrie died from Huntington’s Disease in 1967 at the age of 55.