The University of Oklahoma Press recently released a new book that certainly caught my attention. Copper Stain, by Elaine Hampton and Cynthia C. Ontiveros, should be an excellent read. I was raised on El Paso’s northeast side but moved near ASARCO (the west side) after I turned 18. The smelter’s community plays a small role in my book Frank Little and the IWW: The Blood That Stained an American Family. I thought I would share an old blog post from my Frank Little website, though Copper Stain should tell a broader, poignant story about the people who suffered the most from ASARCO’s legacy. I congratulate its authors! The old posting begins below:

When I was an aspiring college student at the University of Texas at El Paso back in the early seventies, I had to park my car in a designated area beyond some low sand dunes and navigate a beaten trail just south of the dorms before my feet hit pavement. Immediately to my left was I-10, and beyond that, railroad tracks, the border fence, a corralled Rio Grande, and Mexico. On many occasions, my mouth immediately filled with a metallic taste—ASARCO was emitting fumes on these days. While I understood that the dingy-colored boulders and buildings next to I-10 and the university were due to these emissions, I, like many other students, had no idea that the fumes were laden with toxins. The discolored landscape and leaden taste just came with attending UTEP. I also had no idea that my uncle, Frank Little, had arrived near ASARCO over fifty years prior and barely escaped with his life. He likely was targeting Mexican workers who lived in Smeltertown, a poor community on the United States side of the river, that supplied labor for the American Smelting and Refining Company.

When we students parked on a “scenic” overlook above I-10, just below Sun Bowl stadium, we observed the dismal living conditions of Mexicans who occupied an area called “las colonias,” just on the other side of the interstate. Some families lived in ancient adobe buildings, others in shacks, constructed of cardboard boxes, or plywood, if they were lucky. We watched families bathe and get drinking water from the muddy river. In winter months, since wood was scarce, these families burned tires for warmth, sending black plumes of smoke upward. Before anyone seriously talked about pollution, El Paso’s winter inversion was astounding—and it made for spectacular sunsets.

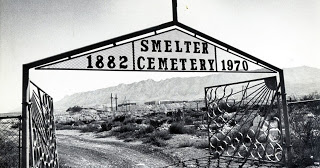

We could also see ASARCO’s Smeltertown, with its plastered-adobe housing, elementary school, and cemetery. Many had died in Smeltertown. The Texas Historical Association reports that by the time the city of El Paso and the state of Texas filed a $1 million suit against ASARCO, charging the company with violations of the Texas Clean Air Act, the county health department found that the smelter had emitted more than 1,000 metric tons of lead between 1969 and 1971. In 1972, tests found that seventy-two Smeltertown residents, including thirty-five children who had to be hospitalized, were suffering from lead poisoning. A 1975 study found levels indicative of “undue lead absorption” in 43 percent of those living within one mile of the smelter and projected abnormal lead absorption in more than 2,700 local children between the ages of one and nineteen years old. Thus, the elementary school was shut down.

“El Paso sought to evacuate Smeltertown, which a local newspaper described as ‘a grimy feudal kingdom spread beneath the Company Castle,’ but many residents resisted. In May 1975, an injunction ordered ASARCO to modernize and make environmental improvements, which eventually cost some $120 million. Against their wishes the residents were forced to move; their former homes were razed, leaving only the abandoned school and church buildings to mark the site of El Paso’s first major industrial community.” Also remaining is the cemetery.

Despite all the attention to ASARCO and Smeltertown, in the 1970s UTEP’s athletic program provided its athletes summer jobs at the refinery. Go figure!

But what about Frank Little? He had arrived in El Paso likely between November 1916 and March 1917, prior to an IWW meeting. Gunmen, company-hired thugs, had jumped Frank, violently kicking him in the abdomen, the cause of a hernia that almost incapacitated him. By the time of the spring Chicago meeting, he was in great pain. Whether Frank just happened to take the El Paso route after visiting my great-great-grandmother or to agitate El Paso’s ASARCO plant and meet with Mexican agitators there is unknown.

In January 1916, Pancho Villa’s raid on a Chihuahuan ASARCO plant sent workers to El Paso’s refinery for protection. The Mexican Revolution had been raging since 1909 as various leaders (Díaz, Madero, the Magóns, Villa, Zapata, etc.) “ate their own.” The IWW had tried to organize labor against American-owned companies in Mexico but also disliked Villa. In Arizona, site of ASARCO’s corporate headquarters, the IWW was about to organize a strike of metal mine workers, and Frank was in charge.

Paid detectives also could have had information regarding Frank’s itinerary and sought him out for their own reasons. A network of spies operated throughout the mining districts. To facilitate encrypted messages, mining companies had implemented code books that spies and operators used when wiring warning of radical activities among camps and the locations of radical organizers. Could ASARCO’s management have received notice of Frank’s whereabouts?

As for ASARCO, the landmark smoke stacks were demolished on April 13, 2013. Crowds of El Pasoans arrived to view the historic event from the UTEP side of I-10. To many, ASARCO’s demise was long overdue. For me, I now feel slightly discombobulated driving on I-10 since the tallest concrete stack was my point of reference for the west side, aside from the Franklin Mountains. But for many Mexican and Mexican-American families, its destruction marks the end of a poverty-filled era, characterized by illness and death during the tenure of an American-owned corporate giant.